Capt. Lee Stuckey

U.S. Marine Corps Capt. Lee Stuckey’s military service has been one of great valor. He’s been awarded the Purple Heart for wounds received in Iraq, a Bronze Star, U.S. Navy and Marine Corps commendation medals with a “V” Device for actions of valor during combat, and a Combat Action Ribbon, among others.

But those decorations came at a high cost.

“I got to a point one night [where] I didn’t want to live anymore,” Stuckey recalls. “I’d been on six different deployments, four combat deployments, been blown up, had my best friend get killed, lost Marines, lost soldiers in different deployments, put a lot of people on what they call honor flights — flying everybody home after they’d been killed — and I just got tired of living with all this stuff. So I got to that point, and I almost did it.

“I went to pull the trigger on my pistol, and my mom called my cellphone right as I was pulling the trigger. I dropped the pistol and freaked out. I didn’t know what was going on with me. Of course I broke down, and I cried and picked up the phone and told my mom, ‘Hey listen, I’m lost.’”

For Stuckey, the psychological wounds of war were very real. And he’s not alone.

8,000 Suicides Per Year

The statistics are staggering. One in five veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which occurs when one experiences severe trauma or a life-threatening event. It’s heightened when, as in Stuckey’s case, bodily injury accompanies the event. Nearly 300,000 U.S. veterans suffer from PTSD.

“I had one Marine who was really quiet… Finally he started talking, and he didn’t stop for two hours. At the end of it you could tell he had lost weight — the weight was lifted off his shoulders, and you could see that he felt so much better.” - Capt. Lee Stuckey

For some, the disorder is so severe that it leads to suicide. In fact, approximately 22 veterans a day, or 8,030 a year, commit suicide. And while more than 6,000 American soldiers have been lost in combat-related deaths in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars over 14 years, there have been more than 90,000 veteran suicides in that timeframe, according to Stuckey. Simply put, the suicide rate in one year far outweighs the rate of 14 combined years of combat-related casualties.

Sadly, an estimated 50 percent of those living with PTSD never seek treatment, a step that for many could be life-saving. Fortunately for Stuckey, that call from his mother was a sobering one — he realized he had to get help, and he got the rehabilitation he needed.

Photo by Robert Fouts

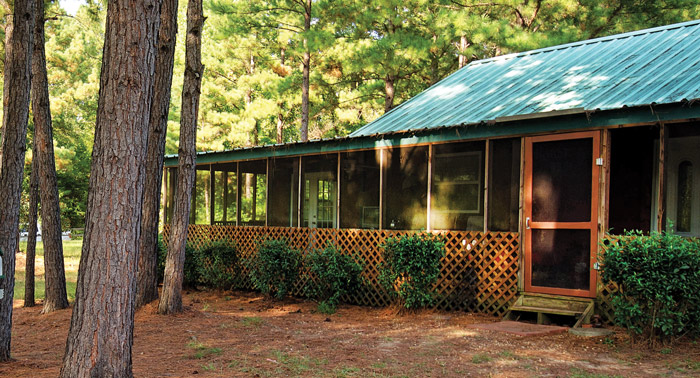

Here on his farm, Capt. Lee Stuckey offers hunting, fishing and conversation as therapies for veterans suffering from PTSD. He plans to build a lodge on the property for year-round use by A HERO program participants.

Therapy on the Farm

Before this experience, however, Stuckey had pursued his dream to farm. With financing from Alabama Ag Credit, he purchased his own piece of Alabama paradise — a 100-acre place ideal for his favorite pastimes of hunting and fishing.

Currently serving with the 2nd Battalion 2nd Marines, he hasn’t found time to do much farming, but the property has turned out to be a blessing. After his near-suicide experience, Stuckey discovered that spending time on his land and in other outdoor excursions was therapeutic. This realization gave him an idea: If outdoor therapy worked for him, it just might work for veterans suffering the same feelings.

Courtesy of A HERO Foundation

Retired Marine Cpl. Justin Gaertner, right, with his brother, David, left, and an A HERO supporter following a hunt in Alabama.

“He worked with me to structure the loan in a way that it was aff ordable. Now, we’re working to build a six-bedroom lodge on the property that will be available to our guys 365 days a year.”

– Capt. Lee Stuckey

Stuckey began reaching out and discovered other veterans still dealing with the trauma of war. Recognizing that many of them would never seek treatment, he invited some to hunt and fish with him on his farm. From that point forward, he realized that his best therapy was to give back to others like him by spending time with them and talking about the things he’d been through. The combination of open discussions and a weekend spent hunting and fishing proved to be the ideal antidote to a very real problem.

During these hunting and fishing excursions, Stuckey employs what he calls “screened porch therapy.”

“I bring these guys in, but you don’t tell them they’re coming in for therapy. But I make an intentional effort to share my story so they’ll open up about what they’re experiencing,” he says. “We sit on the porch, and I talk about everything that I’ve been through, and we go around the room and we just talk. A lot of our stories are about combat, but we tell funny stories too; it’s not all sad. We just talk about the different things we’ve been through, and by the end of it everybody has shared.”

Funding the Cause

Once Stuckey realized the effectiveness of the get-togethers, he made an organized effort to properly recruit and host veterans. In 2010, he organized A HERO Foundation — an appropriate acronym for America’s Heroes Enjoying Recreation Outdoors — to provide others with a way to support the cause.

A HERO hosts several annual events, including a duck hunt in Arkansas, a deer hunt in Alabama each January, a guided hunt in South Africa every March, an Alabama turkey hunt in April and a deepsea fishing trip every August. Other events are held sporadically. Stuckey also has invited members of this veterans’ network to Ultimate Fighting Championship mixed martial arts fights — one of his other passions — and Zac Brown concerts.

He describes A HERO as a judgmentfree zone.

“These guys aren’t lepers, they’re not weak,” he says. “They’re just guys going through a lot of difficult experiences. And if they’re dealing with these kinds of issues, it just means they’re human. Our bodies are not meant to process this stuff naturally.”

A Weight Lifted

Stuckey shares the story of one particular A HERO participant, who was “released” of the emotional and psychological burdens he’d been carrying for nearly a decade when he spent a weekend at Stuckey’s Alabama farm.

“I had one Marine who was really quiet. We all told our stories, and he didn’t say anything — he just listened,” Stuckey recalls. “Finally he started talking, and he didn’t stop for two hours. At the end of it you could tell he had lost weight — the weight was lifted off his shoulders, and you could see that he felt so much better. His whole demeanor had changed.

“He looked at us and said, ‘You know, I haven’t told anyone any of these stories, including my ex-wife who left me with my two kids.’ He opened up about everything. The rest of the two days he was a different person — he was smiling, he was laughing,” Stuckey recalls.

Support From His Lender

Stuckey says that Alabama Ag Credit and his loan officer, Louis Kennedy, have been an integral part of A HERO’s success.

Photo by Robert Fouts

A peaceful fishing hole on Stuckey’s farm is available for use by A HERO participants.

Courtesy of A HERO Foundation

Marine Cpl. Aaron Howell, a lifelong outdoorsman injured in Afghanistan, participates in an A HERO hunt.

“Louis has been awesome,” Stuckey says. “I told Louis, I want to get more land; I want to be able to support more people. So he immediately began helping me look for land. He’d call and say, ‘I’ve found a new tract, let’s go take a look at it; I think it will be perfect.’ Or he would advise about properties he didn’t think met my needs.

“I can’t tell you how many e-mails we sent back and forth trying to secure our last property,” Stuckey continues. “He always took the time to explain everything to me. It’s like he wanted the farm for me and the veterans more than I wanted it — he wanted to make sure I was taking care of these guys. He worked with me to structure the loan in a way that it was affordable. Now, we’re working to build a six-bedroom lodge on the property that will be available to our guys 365 days a year.”

A HERO has supported more than 450 veterans since its inception four years ago. While many charitable organizations retain a percentage of their funds for executives and board members, this nonprofit foundation keeps nothing for management; 100 percent of the funds donated to A HERO go directly to the cause, according to Stuckey.

Courtesy of A HERO Foundation

During an A HERO fishing get-together in Alabama, Clifton Trotter, left, swaps stories with Everett and Alice Cole. Everett is a retired Marine.

“My biggest rule for participants is simple,” he says. “The only thing I ask is that they go out and find two other guys who they know are going through problems, so that they can save their lives and pay it forward.”

– Grace Ellis

To learn more or to contribute online to A HERO Foundation, go to www.aherousa.com.

Mother-Child Bond Stretches Across the Miles

Distance doesn’t diminish the mother-child bond, especially when the child is on the battlefront. Letha Stuckey, whose son Capt. Lee Stuckey served three tours in Iraq, attests to that bond.

“One tour deployed him to Fallujah. Months went by and I had not heard from Lee. One afternoon, with a heavy heart, I decided to leave work a little early. Inside my car, I turned on the radio, which was set to NPR,” she says. “As I left the parking lot, NPR reporter Rachel Martin, host of "All Things Considered," announced that she was interviewing Marines in Fallujah. Stunned, I listened attentively.

“She described the camp, the scorching heat and the sight of Marines jogging. Her reporting then took us to a tent that housed Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) equipment. We were told that a Marine by the name of Lt. Lee Stuckey had learned from personal experience that MMA helped control PTSD. He was committed to teaching other Marines the lessons he had learned. All of a sudden, from more than a thousand miles away, my son's voice came from the radio. I was so shaken that I pulled the car off the road," she recalls.

"It was a wonderful interview," says the proud Alabama mother, "but most important, it came at a time when I most needed it and in an unbelievable way. There is no such thing as circumstance. Everything in life happens for a reason, even though we cannot always determine the why until much later. A parent's connection to their child is a bond that, if nurtured, lasts until the end of our earthly journey."