Photo by Christine Forrest

Making wine is as old as the hills in North Alabama. In this region at the foot of the Appalachians, homemade fruit wine is a local tradition, and nearly 20,000 acres of grapes once grew along the Georgia state line northeast of Talladega. The scenic wine country even attracted trainloads of tourists in the days before Prohibition. A century later, the industry is flourishing in the hands of a new generation of winemakers. Alabama wines in an array of styles are found in stores and on menus, and tourists are once more taking to the scenic byways to enjoy the wine and hospitality at local tasting rooms.

Jim Tollison, vice president and branch manager at Alabama Farm Credit's Talladega office, says that when he's looking for a thank-you gift that says Alabama, wine is high on the list. Located near the heart of the state's wine industry, his office provides financing for three wineries — each with its own personality and business model, and all growing in volume.

Fruit and Muscadine Wines a Southern Speciality

Traditionally, wines made with muscadines, peaches and berries have represented the bulk of Alabama's production.

"Muscadines are a cultivated wild grape. They have so much vigor," says Charles Brammer Jr., whose family owns Morgan Creek Vineyards and Winery. Muscadines grow well in the Southern sun and humidity, and are rich in antioxidants that impart health benefits to wine, sports drinks and nutritional supplements, adding to the list of uses for the winery's grapes.

Other grapes with American ancestry also grow well in the region. They don't even need the richest soil.

"This soil is good for nothing, which means it's good for grapes," jokes Burt Patrick of Ozan Vineyard & Cellars. His Norton grapes are thriving on the rocky slope below his recently expanded winery, but when he planted his first vines, reliable information on cultivating grapes in the region was in short supply.

That's changing, thanks to research that could give the Southern wine industry a major boost.

New Grape Varieties on Horizon

What really has winemakers talking are new European Vitis vinifera cultivars that are taking on the disease resistance of their American cousins.

At White Oak Vineyards, which produces Southern Oak Wines, winemaker Randal Wilson is already making room for them in his vineyard. "Muscadine and fruit wine is a unique category. No one in California is making it," Wilson says. "And our Norton wine has won a lot of awards. But with these new grapes, we're going to be able to make some world-class wines."

Bred at the University of California, Davis, and planted at a research center south of Birmingham in 2010, three V. vinifera cultivars are yielding very encouraging results, says Dr. Elina Coneva, an Auburn University associate professor and Extension specialist. Not only are they showing resistance to Pierce's disease — which can wither many grape varieties in the South — they have also produced some well-rated wine.

Coneva says she is getting many phone calls about the grapes from Alabama wineries, which have doubled in number since 2006 and now total 14.

It's easy to see why new vintners are attracted to a field that blends business, science, craft and hospitality.

"There's a lot of growth in wineries and breweries in the state of Alabama," says Brammer. "This business has so many facets. We never get bored."

There's even some time for freedom.

"You don't have to be here every minute," says Patrick. "You can turn the lights out and leave, and the wine's happy."

Morgan Creek Vineyards and Winery

Great things can come from small beginnings. Just ask the Brammer Family.

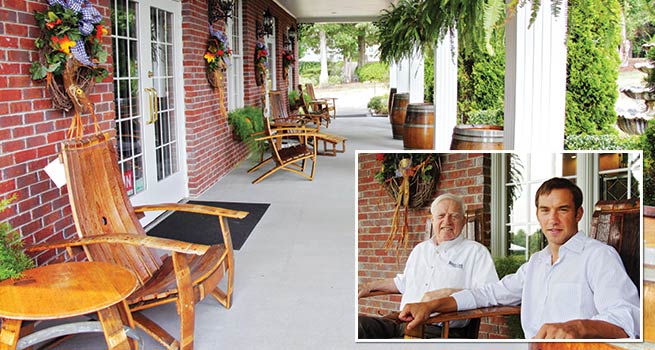

Wine barrel furniture invites visitors to spend some time outside Morgan Creek Vineyards and Winery's tasting room. The family-run business was started by Charlie Brammer, his son, Charles Jr. and wife, Mary. The father and son are pictured at right.

Photos by Christine Forrest

The owners of a pick-your-own farm in the 1990s, the Brammers followed a long Southern tradition when they made homemade wine from their berries and native muscadine grapes.

It could take all day to extract a few gallons of juice from the farm's leftover fruit using a small press, but the effort was worth it. Soon they were making wine commercially, and their business, Morgan Creek Vineyards, has grown into Alabama's largest winery, producing almost 15,000 cases of wine a year.

Nine acres of pick-your-own fruit are still an essential part of a business built as much on experiences as on a product.

"Early on, we got some good advice," says Charlie Brammer, who opened the winery in 2000 with his wife, Mary, and son, Charles Jr. "A friend told us, 'Don't plant the vineyard all the way to the winery. You're going to need the parking space.'"

Agritourism keeps the lot full. Visitors head to the vineyard near Birmingham for wine tastings, tours, picnics, concerts, weddings and fireworks, and in September, a grape stomp — complete with an "I Love Lucy" lookalike contest — draws thousands. For the Brammers, a day at the office might mean crushing grapes, selling furniture that they make from oak wine barrels or hosting 200 Chinese car dealers on a side trip from the nearby Mercedes-Benz plant.

Capturing the Fruit Flavor

The wines are made behind the tasting room in Morgan Creek's elegant brick headquarters. Charles Jr. calls the automated system that fills 1,500 bottles an hour the heart of the winery operation, but its soul has to be the traditional flavors that appeal to Southern consumers. Morgan Creek specializes in wines made with peaches, blueberries and muscadines, native grapes with a distinctive floral aroma.

"We're trying to capture the fruit flavor," says Charles Jr., who owns a business that distributes Morgan Creek's wines. "We have a great niche. A typical store might have hundreds of chardonnays and cabernets, but few wineries do what we do."

Although the winery produces 14 wines ranging from dry to sweet, consumers make their preferences known.

"This is the land of sweet tea and Coca-Cola," he says. "Our sweet wines are our best sellers."

Expanding Territory and Production

The wines are sold in hundreds of Publix, Piggly Wiggly, Target and Whole Foods Market stores in Alabama and Missississippi, and the winery can ship to consumers in 21 more states through its website.

All it would take to expand is more fruit and more storage, and the Brammers have plans to plant 95 more acres of muscadines. When they financed the purchase of more cropland recently, they returned to Alabama Farm Credit's Talladega lending office, managed by Jim Tollison, who helped them finance the winery.

"I learned a lot about business from making loans with Jim — and I used to make loans when I was with Allstate," says Charlie, a retired insurance agent. "It's been very satisfying to work with them."

"Early on, you could see where the business was going and what they were going to do with it," says Tollison. "They really enjoy working together as a family. They're great hosts and entertainers."

Ozan Vineyard and Cellars

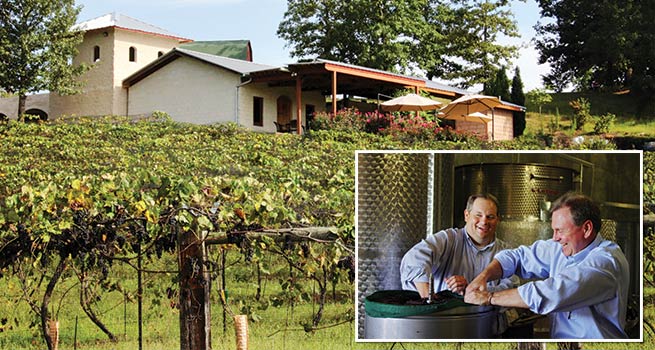

Perched high on a sun-drenched hillside, Ozan Vineyard and Cellars is like a little piece of Tuscany in Shelby County, Ala.

Jim Tollison of Alabama Farm Credit's Talladega branch office, left, and Burt Patrick, winemaker at Ozan Vineyard & Cellars, have their hands full in Ozan's new production facility. They're finding out what pomace — the skins and seeds left behind after grapes are pressed — feels like.

Photos by Christine Forrest

Purplish-black grapes hang from four acres of trellises on the slope, while visitors relax on shady terraces outside the tasting room, sampling some of Ozan's dozen or so wines.

For winemaker Burt Patrick, his family's farm in Calera, south of Birmingham, was the perfect place to capture the essence of the small family-run wineries and European hideaways he discovered during his career importing and exporting paper.

He planted his first vines in 2001 to experiment with grapes that produce the dry wines he prefers, and calls it divine intervention that he tried Norton, also known as Cynthiana, an American grape that has thrived at the site.

The Nortons are used in a red wine that Patrick ages in oak barrels for several years. He also produces European-style red, white, rosé and peach wines made with fruit from other growers, as well as a scuppernong white wine made with regional muscadines.

A Destination Business

Ozan wines are available in restaurants and wine shops in Alabama and Mississippi, and the winery also has a following among tourists, who take home 5,000 souvenir wine glasses a year. Located not far from Birmingham, Tuscaloosa and the Mercedes-Benz plant in Vance, Ozan hosts weekend tastings and up to 20 events a year, including several weddings. It's also a stop on the Heart of Dixie Railroad Museum's train excursions, which bring thousands to the winery each year for Easter egg hunts, a pumpkin patch and a train robbery re-creation ("The good guys always win," says Jim Garnett, the museum's president).

At an October barrel tasting, guests sample wines before they're bottled, providing valuable feedback.

"People like local products, and Norton is a grape that grows well here," says Patrick, who last year received a Value-Added Producer Grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to market wine made with his fruit. "There's an opportunity for producers to customize products for local palates.

"Agritourism is a key component to this. The wine business is a destination business."

Tasting Room Grows with Winery

Ozan became an even better destination this spring, moving into a 2,500-square-foot addition that Patrick designed with ample space for events and an energy-efficient production facility built into the hillside — similar to the European wine cellars that inspired it.

"With the financing of the winery, we've gone from a modest operation to a substantial one," says Patrick, pulling out his cell phone to show a photo of the crane that placed the concrete-plank ceilings. "Our previous facility could only produce 1,000 cases of wine a year, but this was designed to produce 5,000. It could one day support a fully operational warehouse on top."

"There aren't many Farm Credit projects that require a crane," says Jim Tollison of Alabama Farm Credit, Patrick's loan officer for more than 10 years. "Burt is always thinking months and years ahead." "The wine business is all about the future," Patrick replies.

White Oak Vineyards

For Randal Wilson, making wine is an art and a science.

Randal Wilson, left, expanded the tasting room at White Oak Vineyards in 2010 with a 2,000-square-foot, energy-efficient production facility. He's now adding 10 acres to his vineyard.

Photos by Christine Forrest

Walking into his vineyard high in the Choccolocco Valley, east of Anniston, Ala., he describes how the topography, minerals, long growing season and cool air at this beautiful site work together to ripen grapes to their peak.

"We try to make top-quality wine, and it starts right here," says the retired USDA soil scientist and certified crop advisor. "On slopes like this, we still have the complete soil profile. That's been a real gift. If you don't have good fruit, you don't have good wine."

The Semmes, Ala., native didn't foresee becoming a winemaker when he took a class in enology and viticulture at California Polytechnic State University, where he went to college on the GI Bill after serving in the Navy. But after moving here with his wife, Dr. Dana Davis, in the 1990s and planting his first grapes, the idea captivated him.

Sustainability Indoors and Out

He opened the winery and tasting room in 2004 and has been expanding ever since, adding a new production facility in 2010 and halving his energy bills - one of the biggest expenses for Southern wineries — through green building technologies such as concrete walls, heavy insulation, natural lighting and ductless air-conditioning. He gets a head start on AC season by circulating near-freezing irrigation water under the foundation in the winter, chilling the very earth under the wine tanks.

Sustainability is also the watchword in the vineyard, says Wilson, who is on the board of the Alabama Sustainable Agriculture Network. Managing pests and diseases with minimal inputs not only makes him more competitive, he says, it also protects the vineyard ecosystem and supports his bottom line for the long run.

Building Flavor From the Ground Up

That seven-acre vineyard is the foundation of his Southern Oak Wines label, which includes wines made with American muscadine and Norton grapes, French-American grape hybrids, blueberries and peaches. Each year Wilson produces up to 1,500 cases of wine, sold at Publix, Winn-Dixie and other major grocery stores in Alabama.

He's most proud of his sparkling muscadine — the state's only sparkling wine — and Norton, a dry red wine chosen to represent Alabama in Epicurious.com's "The United States of Wine" list last year.

But his energy kicks up a notch when he talks about a new frontier: elite cultivars that resist Pierce's disease, the bane of European grape varieties in the warm, humid South. Improved varieties bred by the University of California, Davis, and tested by Auburn and Texas A&M universities could open the door to producing chardonnay, petit sirah and similar wines in the region.

"These experimental varieties have been successful beyond all expectations," says Wilson, former president of the Alabama Winemakers and Grape-Growers Association. "It's a game changer for us."

This year Auburn asked Wilson to produce some wine with its test grapes, and he and fellow winemaker Jules Berta hope to be the first in the eastern U.S. to grow the improved varieties commercially. They have written a proposal in the hope of obtaining foundation plant materials from UC Davis, and are already preparing a new 10-acre mountainside vineyard on land that Wilson recently purchased with financing from Alabama Farm Credit.

"Randal can talk for hours about what makes a good wine," says Jim Tollison, branch manager of the association's Talladega office. "He loves what he does."

"There's nothing quite like being a farmer and small business owner. It's challenging and exciting," Wilson says. "Farm Credit is making these post-retirement years some of the most rewarding in my life. Jim and the staff are so professional. They're the best financial people I've ever worked with."

— Staff