When W.S. and Mary Smith of Grayson County, Texas, signed their loan with the Van Alstyne National Farm Loan Association (NFLA) on May 22, 1917, it is doubtful they realized they were making history.

Like many of their neighbors, the Smiths simply wanted a better deal for their farm loan than the 8 percent interest rate they were paying another lender. They found it in the 5 percent rate offered through the new lending cooperative in their rural North Texas community. And in so doing, they became the first Farm Credit borrowers in the original Tenth Farm Credit District — now commonly referred to as the Texas District.

Since that first loan closing nearly 100 years ago, thousands of farmers, ranchers, agribusinesses and rural homeowners have realized the value of doing business the cooperative way, with a lender as rooted in rural America as the very people and businesses that own it.

On a milestone anniversary, it is natural to tout the numbers — the loans made, the growth in service lines, and the capital and assets. But the real story behind Farm Credit’s first 100 years resides in the stories of the people whose lives and livelihoods have been improved by this cooperative financing organization. With Farm Credit, they have fulfilled youthful dreams to start a farm, if only someone would give them a chance. They have raised families in country homes that other lenders thought too Made for Farmers, Owned The storiy of Farm Credit, rural America’s unconventional. They have found a financing partner who could see their vision for a new innovative market, and helped them fulfill it. They have kept family farms in the family, and rural communities vibrant.

Farm Credit is composed of people like the Schwiening family of Sonora, Texas, the first PCA borrowers in the district, who developed an outstanding herd of Aberdeen-Angus cattle. Then there are success stories like that of J.R. Canning of Eden, Texas, whom Farm Credit helped transition from a propertyless cowboy to a prosperous 125,000-acre rancher with thousands of head of livestock. Consider, also, the 21st-century success story of Brenton Johnson, who started Johnson’s Backyard Garden outside Austin, Texas, with Farm Credit financing and grew it into the largest Community Supported Agriculture organic vegetable farm in the nation. It is people like these and thousands of others whose stories weave the fabric that is Farm Credit today.

Farm Credit continues to be the financial engine that has kept American agriculture running for 100 years. Its story is as diverse and evolving as agriculture itself. The cooperative credit system envisioned by Congress 100 years ago has stood the test of time. As we celebrate this milestone and look to the next, we salute the borrowers, directors and employees past, present and future who are the lifeblood of Farm Credit.

Planting the Seed

Early 1900s through 1916

It is difficult to imagine how different our country was just 100 years ago. The Civil War had ended in 1865; battlefields had gradually become cornfields and pastures again; and the availability of free land through the Homestead Act of 1862 meant that even more soil could be cultivated. It was against this backdrop that the farm picture — and with it, the need for credit — began to change dramatically.

At the turn of the century, farming underwent a massive expansion. From 1860 to 1910, the number of American farms more than tripled, from 2 million to 6.4 million. Early farm mechanization required money, which was scarce in rural areas. Farm products flooded the market faster than the supply of gold needed to back American dollars, leading to a panic and calls for a banking system overhaul.

The farm population at the time accounted for one-third of the U.S. population, a sizable voice that could not be ignored by elected leaders. The farm press carried powerful clout, and editorial campaigns by farm newspapers such as Southern Farming promoted the concept of cooperative finance and, specifically, land banks in every state.

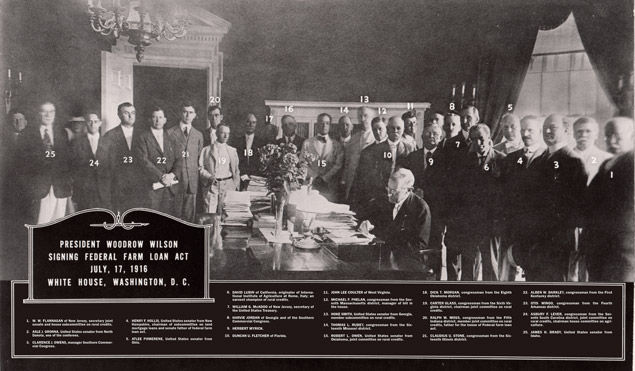

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt established a Country Life Commission that recommended a cooperative credit system, and soon politicians of every stripe were adopting the call for strong rural credit legislation. By 1913, three congressional commissions were studying European farm financing methods such as Germany’s 140-year-old Landschaft system. Their reports led to some 70 rural credit measures introduced into the 63rd Congress, each presenting its own solution. A joint committee resolved the differences into what ultimately passed as the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916. The compromise legislation planted the seeds of the Farm Credit System — providing for land banks to be owned by farmers, and joint stock land banks to be owned by investors.

Establishing Roots in the Post-WWI Economy

1920s to 1933

At the same time that the newly formed Federal Land Banks (FLBs) were establishing roots, World War I was gripping the globe. Food was in demand to feed war-torn countries, and prices for agricultural products and farmland were high. By the postwar early 1920s, however, the U.S. had entered a recession, and increased production by European farmers had reduced the foreign demand for American farm goods. U.S. farm families found themselves again in financial crisis as land and commodity prices slid.

The young Federal Land Banks felt the pain, with increasing numbers of their loans becoming delinquent and many borrowers simply abandoning their farms altogether, creating a growing inventory of foreclosures. This was the environment in place when the stock market crashed on Oct. 29, 1929. The impact on rural communities was severe. Rural banks closed, effectively leaving farm families without the savings they had put away to make their mortgage payments. Farm foreclosures became a weekly ritual on county courthouse steps, and Land Bank business slowed. In just 10 years, the fledgling lenders’ loan volume fell nearly 90 percent.

Complicating farmers’ plight was their lack of credit sources for operating capital. Dependent on deposits, rural commercial banks had little cash to lend. Farmers often were required to pay off loans in 30 to 60 days — an unrealistic expectation for crop and livestock cycles. Once again, elected leaders. federal commissions were established to research solutions. Elements of three different legislative proposals came together in the Agricultural Credits Act of 1923. The legislation established 12 Federal Intermediate Credit Banks (FICBs), to be funded by U.S. Treasury investments.

The FICBs could discount funds to commercial banks for agricultural financing purposes, as well as lend directly to agricultural cooperatives. At last, the farm industry had a reliable source of financing for maturities of six months to three years.

However, the FICBs were not leveraged to their full extent due in large part to strict requirements that farmers pay back loans shortly after harvest, rather than hold crops for the optimum market price. It would be much later, 1956, before farmers would own the banks and replace government capital with their own.

Financing for Farmer Cooperatives

1930s

The concept of doing business cooperatively was nothing new for farmers in the 1930s. The California Fruit Growers Exchange — now known as Sunkist Growers Inc. — was one of the early pioneers in the movement to help farmers buy higher quality supplies at lower cost and eliminate the middleman. Cotton gin cooperatives on the Texas High Plains were operating, as was a dairy cooperative in Plainview, Texas, serving New Mexico and Texas farmers.

But dependent primarily on their own members’ financial resources to invest in them, and with commercial banks hesitant to lend to them, cooperatives found it difficult to grow. In addition, marketing cooperatives faced antitrust law restrictions until the early 1920s, when the Capper-Volstead Act opened the door for farmers to cooperatively market their products. Soon President Herbert Hoover made good on his campaign promises to solve farm problems and, with Congress, formed the Federal Farm Board. The Plainview dairy cooperative was one that received funding through the board, but by the start of the Great Depression, the Farm Board had lost two-thirds of its funds.

Under newly elected President Franklin Roosevelt, the remaining Farm Board funds — along with the Land Banks, Federal Intermediate Credit Banks and all other federal agricultural credit agencies — were placed under the regulation of the Farm Credit Administration essentially forming the Farm Credit System. Joining them were 12 regional banks for cooperatives, one in each of the Land Bank districts. The Houston Bank for Cooperatives began operations in 1933.

Technology, Mechanization Come to the Farm

1900s to 1930s

While credit continued to be a challenge, technology, education and mechanization were beginning to bring massive changes to farming and farm life.

In 1914, the Smith-Lever Act had created the Cooperative Extension Service to bridge the gap in information flow from recently formed land-grant colleges to farmers in the field. As a result, farmers were exposed to new technologies, and farming methods were being shared at land-grant institutions across the country.

Farm-to-market transportation and onfarm equipment would soon see a major transformation as well. Henry Ford’s Model T debuted in 1908, and Ford had more orders than he could fill. His resulting mass production techniques changed the face of industrial production, benefiting entrepreneurs such as Ed Nolt, who began large-scale production of the oneman automatic hay baler in 1939. Ford and many others had been experimenting with gas-powered tractors since about the turn of the century, and by 1920 gasolinepowered tractors were not uncommon on American farms.

In 1930, 58 percent of U.S. farms had cars and 34 percent had telephones, but only 13 percent had electricity.

Arguably one of the most significant changes to farm life, though, came in 1936 when President Roosevelt established the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). Over the next two years, 100,000 miles of new power lines brought electricity to 220,000 farms at a cost of $950 per home. In Texas, young congressman Lyndon Johnson led a grassroots effort to secure $1.3 million in REA funding to construct more than 1,700 miles of Texas Hill Country power lines, the largest single loan granted by the administration at the time. In November 1939, electricity started to flow through the lines, and Pedernales Electric Cooperative soon became the nation’s largest electric cooperative.

Today, agriculture requires enormous amounts of capital. Technology has revolutionized farming and agribusiness. Yet, Farm Credit has continued to rise to the challenge of providing sound, dependable credit to agriculture and rural America.

Production Lending Co-ops Born of the Depression

1930s

The stock market crash of 1929 exacerbated a decades-long decline in agriculture and set off the Great Depression, throwing thousands of farmers into bankruptcy and strangling the Farm Credit System’s ability to finance agriculture. Farm prices plummeted, rural businesses were shuttered and numerous banks across the country closed.

With the price of cotton dropping to a record low of 5 cents a pound by 1931, many farmers could no longer survive on farm income and moved to the city. But nonfarm jobs were scarce. In Alabama alone, nonfarm employment fell 15 percent between 1930 and 1940.

In the Texas Panhandle, northeastern New Mexico and elsewhere in the southern Great Plains, powerful dust storms engulfed a region that would become known as “The Dust Bowl,” exposing the soil where native grasslands had been cultivated for wheat crops. Thousands of families packed up their meager belongings and left seeking work elsewhere, having lost their crops, their livestock and their land.

In 1933, Congress passed two laws affecting the future of Farm Credit. One piece of legislation authorized the Land Banks to issue up to $2 billion in U.S. Treasury– guaranteed farm loan bonds to make new mortgage loans and to refinance existing farm mortgages. The other revamped the Federal Intermediate Credit Banks and established a short-term credit delivery system through locally owned Production Credit Associations (PCAs).

Farm operating capital was in high demand from the Depression through World War II. The nation’s Production Credit Associations made loans totaling $107.2 million in 1934 and $614.6 million in 1946.

As producers discovered the benefits of doing business with a financing cooperative that they owned — and that truly cared about their success — Farm Credit became the trusted financial partner of generations of rural Americans. By 1968, all of the Farm Credit System lending entities had repaid their federal capital debt and were completely owned by their borrowers.

Production for War Years

1940s

Three days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, officials of the Banks for Cooperatives met in Washington, D.C., as the entire Farm Credit System prepared to fight inflation and feed a nation at war. The United States’ entry into World War II brought new priorities for Farm Credit: keeping farming and ranching as efficient as possible, providing the cooperative credit necessary to produce processed foods and other war materials, and restraining any land boom that might result from wartime inflation.

Production Credit Associations and the Banks for Cooperatives were called into action to finance crops that were in short supply. They reminded members that, for the duration of the war, they were “soldiers of the soil.” Across the country, PCAsponsored Victory Calf and Pig Days marketed much-needed meat with payment in War Bonds. During the war years, PCA financing grew little due to the short supply of farm equipment. However, business at the Banks for Cooperatives grew more than 100 percent, reflecting cooperatives’ ability to meet farmers’ needs for scarce farm supplies.

Land Bank employees’ expertise was called into action, as well. The federal government acquired farmland and ranchland for wartime uses — training camps and artillery ranges, air bases and ammunition dumps. Land Bank staff appraised the properties, and after the war they led the effort to return more than 1 million acres of surplus land to its former owners, veterans, government entities and nonprofit groups.

By 1945, U.S. agriculture was prospering, and Farm Credit was finally recovering from the Great Depression.

Post–World War II: Independence and Entrepreneurship

1950s and beyond

By the early 1950s, Congress and President Dwight D. Eisenhower were lending support to a decade-long effort to make the Farm Credit Administration an independent agency and bring Farm Credit closer to the cooperative ideal. The Farm Credit Act of 1953 gave Farm Credit members more power to elect their leadership, and instructed Farm Credit to plan for full borrower ownership.

In addition, the legislation moved the Farm Credit System’s policy oversight function from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to an independent, membernominated Federal Farm Credit Board. One of the new board’s initial tasks was to present Congress with a plan to make farmers the full owners of the System by replacing government capital with farmerowned capital. Many years later, Texas made its own unique contribution to the board when, in 1994, Marsha P. Martin, former Farm Credit Bank of Texas senior vice president of public affairs, became the first woman to head the Farm Credit Administration.

Under the leadership of the new board, the number of farmers and cooperatives served by Farm Credit grew rapidly, as did loan volume. The farmers, ranchers, agribusinesses and cooperatives that made up the member-owned lending network composed what Farm Credit Board Chairman Marvin Briggs claimed to be the largest cooperative organization in the world.

In the Tenth District, Farm Credit had taken on an air of permanence and power, symbolized by the imposing edifice of the bronze-trimmed limestone Federal Land Bank Building at 430 Lamar Street in Houston, Texas, also home to the Federal Intermediate Credit Bank of Houston. By 1979, the banks’ names were changed from Houston to Texas, more accurately reflecting their service territory. Rapid loan volume and personnel growth created the need for more office space. The banks sold their Houston property for $47.5 million during the height of the Houston real estate boom, a record price per square foot in Houston’s real estate history. The funds were largely reinvested in a new headquarters in Austin in 1982, with the remainder injected into the banks’ capital and lending operations.

Innovating and Setting Precedents in Lending

1960s and beyond

The 1950s and 1960s formed a period of industry transformation heralded by new farming methods, technological advancements and equipment innovations. During this Second Agricultural Revolution, equipment brought efficiencies and speed to tasks once done by farm labor. The labor force dwindled, while the capital needed to run a farm or ranch increased. Farm Credit was there to fill the growing needs of an evolving industry.

Farm Credit set the precedent for many lending practices and products later adopted by commercial lenders and today considered commonplace. Credit life insurance was one such innovation, as was the practice of amortizing loans. Before Farm Credit, farm mortgages extended three to five years at most, at which time all principal was due. Commercial farm mortgages created a continual need for farmers to renew their loans, with costly renewal fees every few years and no certainty of success. In contrast, Federal Land Bank Associations offered loans up to 40 years, annual or semiannual payments, and options for amortizing the debt.

Likewise, truth-in-lending policies were a part of Farm Credit lending processes long before the public demanded truth-inlending laws for all lenders. PCAs introduced the idea of lines of credit to farmers, unheard of at the time. Recognizing farmers’ needs for longer term loans, PCAs also introduced intermediate-term financing for major capital expenditures.

Even the basic tenets of loan evaluation, which today all types of lenders rely upon for credit decisions, originated through Farm Credit. The “5 Cs of Credit” can be found in early Farm Credit loan officer training handbooks. They stress the importance of evaluating the key elements of an applicant’s character as much as his or her capacity to repay the debt, collateral, capital and conditions surrounding the loan.

Farm Credit Expands to Meet a Changing Market

1970s and beyond

By the early 1970s, with government capital repaid and ownership fully in the hands of farmers and ranchers, Farm Credit member-owners began to study ways to meet the rapidly changing credit needs of the agricultural industry. Thousands of individuals and groups weighed in with ideas and suggestions. Among the recommendations were several consistent themes:

- • Continue to serve farmers and cooperatives while making credit available to farm-related businesses and competent young farmers

- • Help keep rural America healthy by financing nonfarm needs such as rural homes and utility systems

- • Employ credit standards, reliable funding sources and cooperation among individual Farm Credit entities to ensure a strong financing system

The input of the nation’s farmers, ranchers and agribusiness leaders was heard, and Congress passed the Farm Credit Act of 1971, dramatically broadening the System’s ability to serve agriculture and rural America. Three amendments to the act in 1980 further expanded the System’s lending authority, providing for the creation of service organizations and recognizing young and beginning farmers’ credit needs.

For the first time, PCAs and FLBAs could make nonfarm rural home loans. They could now serve commercial fishermen — who within only four years would borrow $37 million. They could offer creditrelated services and lease financing. And, they created new programs to help young, beginning and small operators establish equity, credit history and viable farming operations. Today, the Farm Credit System has over $27 billion in loans outstanding to farmers age 35 and younger.

At the end of 2015, the Farm Credit System had nearly 188,700 loans outstanding to young farmers, totaling $27.1 billion.

The expansion marked yet another milestone in Farm Credit’s history of adapting to the changing needs of the nation’s food producers and marketers. What once had been an underserved market with few reliable, affordable commercially available options now had a full-service rural and agricultural financing source owned and led by farmers themselves.

The Consolidation Years

1980s

The 1970s were boom years for American agriculture and for Farm Credit. Agricultural exports — and in turn, farm incomes and commodity prices — soared as trade barriers were lowered. The expanded lending authorities granted to Farm Credit in the 1971 act, coupled with low interest rates, led to more loans for farmland purchases to farmers who were counting on continued strong markets and low rates.

By the early 1980s, however, a severe global economic recession brought the boom to a halt. Farmland values dropped by more than half in some regions, and overproduction forced farm commodity prices down. Commercial banks, too, were struggling. As the prime rate rose to 20 percent in the 1980s, bank failures escalated. By 1982, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. had spent $870 million to purchase bad loans as it tried to keep banks afloat.

Farm Credit likewise began to experience serious problems. Farm foreclosures made near-daily headlines. In the midst of this extended farm debt crisis, Congress passed the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987, authorizing up to $4 billion in federal loans to the System, while requiring it to reorganize to become a leaner, stronger cooperative financing organization.

Under pressure from the ongoing farm crisis, many Farm Credit entities already were consolidating to achieve increased efficiency — among them the Tenth Farm Credit District banks. In July 1984, the three Texas banks announced plans to become the Farm Credit Banks of Texas under single management. Within six months of the 1987 act’s passage, each district’s Federal Land Bank and Federal Intermediate Credit Bank, except in the Jackson District, merged to become a Farm Credit Bank, combining the long-term and short-term lending functions together.

In the Jackson Farm Credit District, the 1980s farm debt crisis hit the Land Bank especially hard, eventually leading the Farm Credit Administration to place the bank in receivership in 1988. In February 1989, the Farm Credit Bank of Texas paid $1 billion to purchase approximately 17,000 loans from the FLB of Jackson in Receivership, extending the Texas bank’s charter to provide long-term credit in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi.

The last remaining FICB, the FICB of Jackson, merged with the Farm Credit Bank of Columbia, later renamed AgFirst Farm Credit Bank.

Soon, stockholders of the Texas Bank for Cooperatives voted to join with 10 other banks for cooperatives to form a single Bank for Cooperatives to serve the nation’s agricultural cooperatives. CoBank was created in 1989 with $12 billion in assets, $9 billion in loans outstanding and $807 million in capital, and in 2012 merged with U.S. AgBank.

In 1990, the Tenth District expanded to New Mexico, when member-borrowers of Albuquerque Production Credit Association voted to re-affiliate with the Farm Credit Bank of Texas as their association’s funding source. Two additional New Mexico PCAs soon followed suit, as did Northwest Louisiana PCA.

Preparing for the Future

1990s to 2000s

The 1990s began an extended period of merger mania in corporate America, as businesses looked for competitive advantages and greater corporate earnings. Commercial bank mergers were rampant, and other large corporations joined forces as well.

In Farm Credit, the 1987 act had opened up new opportunities for memberborrowers to also choose new structures and alignments to best meet the needs of local farmers, ranchers and agribusinesses. In addition to directing the mergers of FICBs and FLBs in each Farm Credit district, the act authorized the voluntary mergers of Production Credit Associations with Federal Land Bank Associations. The resulting organizations, Agricultural Credit Associations or ACAs, became direct lenders with two wholly owned subsidiaries:

Federal Land Credit Associations (FLCAs), charged with making real estate loans, and Production Credit Associations, responsible for operating and intermediate-term production loans.

The advantages of integrating lending operations into a full-service business made immediate sense to Farm Credit’s owners, its borrowers. Within less than a decade, most PCAs and FLBAs had adopted the ACA parent structure as the most efficient way to meet members’ credit needs and related financial services.

From the mid-1980s to today, the makeup of the Texas Farm Credit District has changed dramatically. Over that time, its farmer-borrowers transformed dozens of PCAs and FLBAs into 13 ACAs and one FLCA. Today the Farm Credit Bank of Texas provides loan funds and services to these 14 retaillending co-ops and two Other Financing Institutions across Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico and Texas. In turn, these lenders make loans for rural real estate, agribusiness and agricultural production, just as they have for nearly a century.

Financing for an Evolving Industry

2000s to present

By the early 2000s, a stronger economy with rising farm prices and incomes — as well as the federal emergency capital provided in 1987 — had helped stabilize the Farm Credit System. Twenty years after the peak of the farm debt crisis, the Farm Credit System had repaid — with interest — all of the federal capital provided during the emergency, returning it to full borrower-owned status.

Rural America and agriculture have undergone tremendous changes. Agricultural operations today are fewer in number but larger, with increasingly complex financing needs. Technology and equipment to run efficient agribusinesses is costly. Consumers demand a wider variety of food choices, from organics and grass-fed livestock to seafood and local wine, creating new revenue sources for agricultural producers. Rural communities are challenged with maintaining infrastructure to support an aging and shrinking population tax base. At the same time, rising incomes and changing lifestyles have attracted new landowners to niche farms, rural property and country homes.

This new rural America needed a financing partner that understood these changes, and could adapt to meet them. In 1990-91, Congress asked Farm Credit to play a greater role in financing agricultural marketing and processing, as well as financing water and waste disposal systems in rural communities. The Farm Credit Bank of Texas expanded its involvement in the capital markets arena, participating with other lenders in large loans in the food, agribusiness, rural utility and rural telecommunications sectors.

For the past several years, Farm Credit’s share of the agricultural market has continued to grow and now accounts for about 40.7 percent of the nation’s farm business debt. Today the $21 billion Farm Credit Bank of Texas and its 14 affiliated lending cooperatives compose the single largest rural lending network serving Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico and Texas.

As it has done for 100 years, Farm Credit continues to adapt to the evolving needs of agriculture and rural communities with creative, reliable, competitive financing.

—Sue Durio